The hard seltzer category has been on fire lately. Sales increased well over 200 percent in 2019 alone (for more than $1.5 billion in in-store sales) and are projected to continue rising. What about this effervescent new genre of adult beverages has resonated so strongly with consumers? Much of their popularity is due to hard seltzer’s healthier, better-for-you profile.

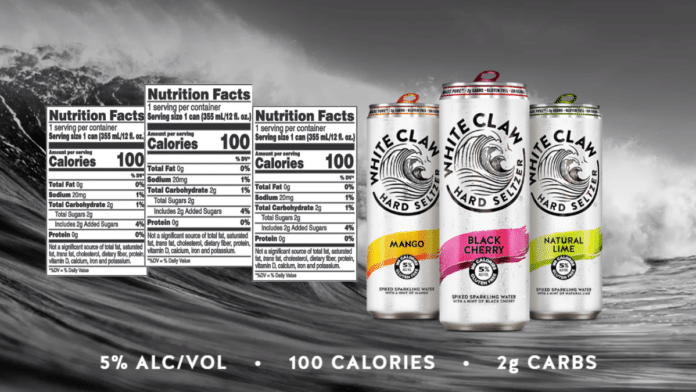

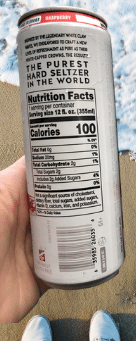

Hard seltzer tends to be lower in sugars and carbs than beer or wine, and around 100 calories per serving on average. Although new imperial options are starting to hit the market, seltzer tends to be lower in alcohol as well, at an average ABV of around five percent or lower. Seltzers tend to be naturally gluten-free and vegan, and many breweries and distilleries are experimenting with craft options made from organic ingredients and premium spirits.

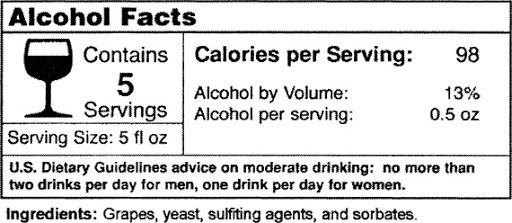

These spiked and sparkling beverages tend to be less bad for you than many beer, wine, and hard liquor options, and they’re happy to show off their statistics. This transparency is due to the fact that many hard seltzer purveyors feel that they have nothing to hide; they’re proud of their cleaner ingredients and (well-deserved) lighter reputation, which are selling points for many consumers.

As a result, many hard seltzer companies are now calling for industry-wide changes, arguing that it’s time for liquor companies to come clean about their ingredients and nutritional information. After all, consumers deserve to know exactly what they are, well, consuming.

Given the focus on labeling in other industries, why has alcohol gotten a pass to this point?

The answer actually relates to the Prohibition era. In summary, alcohol isn’t administered by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) but by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), which was created in order to regulate and tax booze following the repeal of Prohibition, and has never require nutrition labeling.

Public health experts in particular take issue with this situation, and argue that adults who drink consume many more calories from alcohol than they are aware of. Sarah Bleich, a public health researcher at Johns Hopkins, says that these adults regularly consume an average of 400 calories per day from alcohol. “Many adults take in a tremendous amount of calories from alcohol, and they have no idea,” she said.

The rules have changed a bit over the years, and differ depending on the type of beverage as well as the ingredients and alcohol content. For instance, all spirits and any wine stronger than 14 percent alcohol are required to label the ABV, while any beers and weaker wines are not. They may elect to share that information, but it is not enforced at the Federal level. Certain ingredients, like nitrates which stop the growth of bacteria, have to be disclosed on labels.

Some Wine is Regulated by the FDA

Furthermore, certain types of wine under seven percent alcohol fall under FDA jurisdiction, which of course requires labeling. And certain (but not) all allergens are required to be labeled as well. Overall the rules and regulations are quite confusing and a tad arbitrary. It makes little sense that bottled water requires a nutritional label (it’s hydrogen and oxygen and zero calories), yet vodka does not.

Since the 1970s, consumer advocate groups have tried to demand better alcohol labeling no less than six times, yet big alcohol’s lobbyists have proven too powerful. Consumers are likely to drink more if they’re unaware of the nutritional facts.

“We generally know that people don’t have a good sense of nutritional information,” says Bleich. “Americans are really bad at mental math.”

Hard Seltzer Flexes Influence

Now that the hard seltzer category controls a pretty significant share of the alcoholic drinks market, it wants things to change.

As with many facets of hard seltzer, industry leader White Claw has led the charge for nutrition labeling. On its website, one can find nutritional information for ten flavors, organized by serving size. In addition to the standard 12 ounce cans, Black Cherry, Mango, and Ruby Grapefruit all come in 16 and 19.2 ounce tallboys. Its parent company, Mark Anthony Brands, maker a suite of alcoholic beverages, including Mike’s Hard Lemonade and Cayman Jack pre-mixed margarita, includes further health information in its FAQ section.

Truly’s website is similarly organized, providing a standard label as well as information on how its drinks are sweetened (a mix of natural cane sugar and stevia, a calorie-free, plant-derived sugar substitute) and from where the alcohol originates (cane sugar again). With the two biggest names in the hard seltzer category openly sharing their nutrition information, it’s easy to see why so many smaller brands are compelled to follow suit; combined White Claw and Truly account for over 80 percent of hard seltzer sales.

While hard seltzer (like any alcohol) still contains empty calories, the onslaught of lower sugar, carb, and calorie choices still represents progress for consumers who want a hard drink, but with less alcohol or a lighter profile. It may not contain the added benefits of vitamins or minerals (save for Miller-Coors’ Vizzy, which is fortified with Vitamin C) but it has significantly fewer empty calories than most beers or wines, and with less alcohol than hard liquor. Most say it has more flavor than most ultra light beers.

Any alcoholic beverage has its accompanying health risks, but spiked seltzer it is still water based and definitely less bad for you than many of the alternatives. “People are going to feel a little better about consuming a hard seltzer versus a standard beer that’s going to be higher in calories and carbs,” according to Angel Plannels, a spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics. As in most areas of life, people like to minimize their risks, and when enjoyed moderately, hard seltzer represents a safer bet.

The argument against labeling includes advocacy groups concerned that it could normalizes consumption of the product, making it seem like an acceptable food group.

In a letter to the Steven Mnuchin, Secretary of the Treasury, dated February, 2019, three advocacy groups joined forces to appeal for regulation. The Center for Science in the Public Interest, Consumer Federation of America, and the National Consumers League co-authored the letter, which states, “We urge you to instruct the TTB to withdraw the proposed rule and to issue a new proposal providing a mandatory, standardized declaration covering alcohol content by percentage and amount, serving size, calories, ingredients, allergen information, and other information relevant to consumers.”

Regardless of what an individual chooses to drink, many are arguing they have a right to know what it contains.

- Molson Coors Increases NA Foothold with La Colombe Coffee - September 15, 2021

- Half Time Beverage Adds Seltzer and Canned Cocktails Gift Packs - September 14, 2021

- Coming Soon: Great Lakes Agave Twist Ranch Water - September 13, 2021